No respeitado time de compositores dos sambas-enredos das 14 escolas

do Grupo Especial de São Paulo, dois nomes passam longe do estereótipo

do artista nascido em berço do samba. Amigos de longa data, os judeus

Ronny Potolski e Jairo Roizen emplacaram suas composições na Unidos do

Peruche e na Pérola Negra, driblando qualquer preconceito.

Sem

instrumentos musicais associados ao nome de batismo, como Oswaldinho da

Cuíca, Jackson do Pandeiro e Royce do Cavaco; sem referências a orixás,

santos e divindades, como Xangô da Mangueira, Waldomiro do Candomblé e

Paulinho de Ogum; e sem combinações que adicionam 'ginga' à alcunha dos

sambistas, como Neguinho da Beija-Flor, Nenê da Vila e João Batucada; a

dupla viu a galeria de bambas se abrir para seus dois sobrenomes

incomuns neste universo, e genuinamente judeus.

Potolski e

Roizen estreiam no Anhembi com criações desvinculadas da cultura

judaica. As escolas que eles representam tratam em 2016 de temas do

Brasil – país onde ambos nasceram e foram criados. Na Unidos do Peruche,

o enredo reverencia os 100 anos do samba. Criada juntamente com Marcelo

Madureira, Alex Barbosa, Sukatinha, Bagé, Tubino, Igor Vianna, Thiago

Sousa, Gilson, Kaballa, Victor e Meiners, a composição tem sido apontada

por especialistas como uma das três melhores do ano.

Na Pérola

Negra, com outros parceiros, Jairo Roizen emplacou o samba-enredo que

fala sobre a dança. A composição faz um passeio pela história desta arte

e por sua influência no país, e foi feita ao lado de Celsinho Mody,

Guga Mercadante, Nando do Cavaco, Marcelo Zola, Sidney Arruda, Filosofia

Diley e Xandinho Nocera.

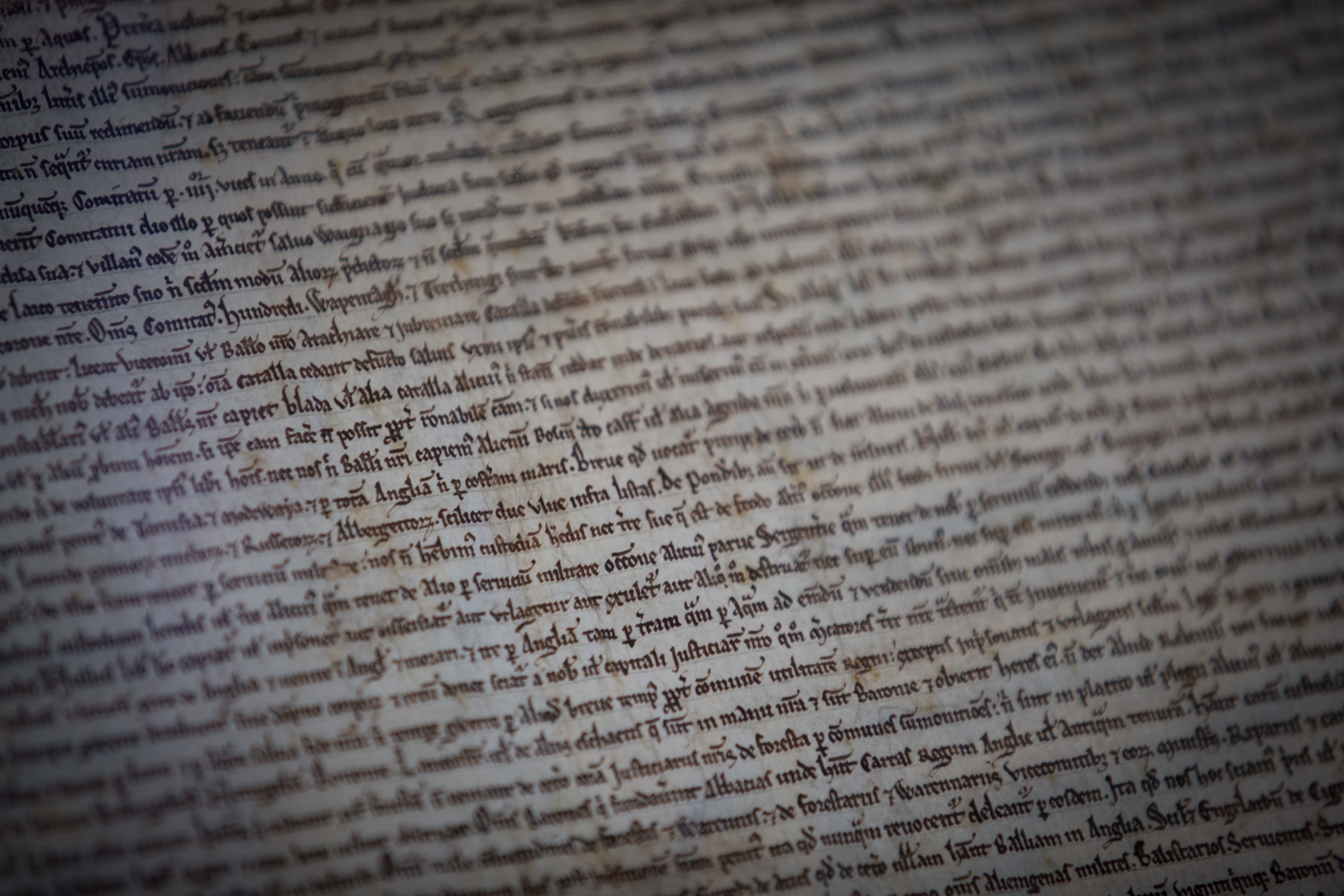

Da sinagoga para a avenida

Jairo Roizen (ao centro) na cerimônia judaica do casamento de Ronny Potolski e Thais Paraguassu

Ronny e Jairo têm muita coisa em comum, a começar pela história das

famílias Potolski e Roizen. Ambas têm raízes na Polônia, Romênia e

Lituânia, e vieram ao Brasil entre a Primeira e a Segunda Guerra Mundial

em busca de oportunidades longe das zonas de conflito da Europa. Mesmo

sem se conhecer, Ronny e Jairo trilharam caminhos quase idênticos em São

Paulo.

Estudaram nos colégios judaicos Renascença e I. L.

Peretz, curtiram o clube A Hebraica, frequentaram a Congregação

Israelita Paulista (CIP) e outras sinagogas, e ouviram os conselhos do

rabino Henry Sobel. Mas só foram se conhecer por meio de uma paixão

brasileira: o samba. Eles foram unidos pelos bastidores das escolas de

samba e por aquele certo glamour do Carnaval que nem todo mundo consegue

entender – nem aceitar.

Os dois meninos judeus foram

apresentados à maior festa popular brasileira ainda crianças. Jairo se

lembra de ter visto o primeiro desfile pela televisão, em 1989, quando

tinha 7 anos. Hoje, com 33, é capaz de reproduzir com detalhes a noite

em que ficou com a avó grudado ao televisor para ver as escolas, que

ainda desfilavam na Avenida Tiradentes. Ronny, 34 anos, também era

vidrado nos desfiles do Rio exibidos pela TV. Sua primeira lembrança é

de acompanhar uma transmissão aos 4 anos de idade. Com 12, quis viver

aquilo mais de perto e passou a colecionar os discos dos sambas-enredo

de Rio e São Paulo.

"A gente não celebra o Natal, mas em dezembro há uma festa judaica

que também é marcada pela troca de presentes, a Chanuká (Festa das

Luzes). Eu sempre pedia o CD dos sambas-enredo", recorda-se Ronny. Dali

até virar um estudioso do Carnaval foi um passo, conhecendo de perto as

escolas de samba de Santos, frequentando a X-9 Paulistana, na Zona Norte

de São Paulo, e indo a desfiles no Anhembi e na Sapucaí.

Para

Ronny, os três melhores sambas-enredo da história do Carnaval paulista

são o da Rosas de Ouro de 1992 ("Non Duco, Duco - Qual a Minha Cara?"), o

da Gaviões da Fiel de 1995 ("O que É Bom É Para Sempre") e o da X-9

Paulistana de 1997 ("Amazônia, a Dama do Universo"). No Rio, seu coração

ainda pulsa quando ouve o enredo da Vila Isabel de 1988 ("Kizomba - A

Festa da Raça"), da Mocidade Independente de 1992 ("Sonhar Não Custa

Nada, ou Quase Nada") e o do Salgueiro de 1993 ("Peguei um Ita no

Norte/Explode Coração").

Formado em Ciências da Computação, com

duas pós-graduações em tecnologias ambientais e engenharia de software,

Ronny ganha a vida como consultor de sustentabilidade. Mas dedica boa

parte de seu tempo a um trabalho não remunerado, de diretor-executivo do

site da Sociedade Amantes do Samba Paulista (www.sasp.com.br) criado há

15 anos com o propósito de manter acesa a chama do samba no estado, um

dia injustamente chamado de Túmulo do Samba.

"Com o site, passei

a viver o Carnaval intensamente", diz Ronny, que também se casou com a

porta-bandeira Thais Paraguassu, hoje na Unidos do Peruche. Começaram a

namorar em 2008, quando ela ainda desfilava pela Tucuruvi, e subiram ao

altar em abril de 2015. A noiva se converteu ao judaísmo e reforçou a

ainda tímida ala dos judeus no samba paulistano.

A enredo da

vida de Jairo não é muito diferente. Depois de amargar a decepção de ver

os desfiles do Grupo Especial de 89 só pela TV, ganhou do pai, como

prêmio de consolação, a oportunidade de ir à avenida Tiradentes no dia

seguinte para conferir ao vivo o desfile do Grupo de Acesso. Naquele

ano, o pequeno corintiano viu brilhar a Gaviões da Fiel. "Ali meu pai

arrumou um problema...Teve que me levar para ver o desfile todos os

anos", lembra Jairo.

Já cursando a faculdade de comunicação da

PUC, passou a frequentar a quadra da Rosas de Ouro, por onde desfilou

durante cinco anos. Formado jornalista, hoje atua como assessor de

Imprensa da Liga das Escolas de Samba de São Paulo e também da Federação

Israelita do Estado de São Paulo, além de apresentar o programa semanal

Shalom Brasil, pelo canal comunitário TV Aberta.

Como o amigo,

também passou a colecionar os CDs de sambas-enredo. Diz que ouve pelo

menos um samba por dia, mas jamais pensou em ser compositor. Sua

experiência mais próxima havia sido na escola, no I. L. Peretz. Em 1995,

quando a Gaviões ganhou o Carnaval de São Paulo com o memorável "Me dê a

mão, me abraça, viaja comigo pró céu...", Jairo resolveu se apoderar da

canção para fazer bonito em um desfile da escola. Para comemorar o

Purim (a mais alegre festa da cultura judaica, que inclui o uso de

fantasias), a classe de Jairo criou até um carro alegórico, que desfilou

pelo colégio com uma música feita propositadamente sobre a base do

samba da Gaviões.

A mão dupla do preconceito

Ronny Potolski e a mulher, a porta-bandeira Thais Paraguassu, da Unidos do Peruche

Em 2009, Jairo passou a fazer parte da diretoria da Pérola Negra.

Como diretor de Carnaval da escola, sugeriu, em 2011, o enredo "Abraão, o

Patriarca da Fé", abrindo caminho para derrubar o preconceito de quem

condenava a presença de judeus no samba. Naquele desfile, 300 dos 3.000

componentes da Pérola eram judeus arregimentados na comunidade judaica

de São Paulo. "Pensei naquele enredo como uma homenagem aos meus avós,

que se orgulhavam de me ver no mundo do samba, apesar da origem deles

não ter nada a ver com isso. Foi também uma forma de retribuir aos

brasileiros o carinho com que receberam todos os judeus fugidos da

guerra", diz Jairo.

Antes, em 2003, a Mangueira já tinha levado

Moisés para a avenida com o enredo "Os Dez Mandamentos: o Samba da Paz

Canta a Saga da Liberdade". Mas a este enredo da Pérola, ele credita um

marco na luta contra o preconceito que, em sua opinião, trafega numa via

de mão dupla no país. O problema é que a tolerância das fantasias que

se exprimem na passarela não reflete a realidade do mundo real. Tanto

assim que, apesar dos esforços, judeus mais ortodoxos veem o Carnaval

como uma festa que fere princípios culturais e religiosos do judaísmo. E

sambistas mais conservadores ainda se valem de alguns estereótipos para

acreditar que um sujeito loiro, branco, de olhos azuis e influência da

cultura hebraica não possa fazer samba, viver de samba.

"Ganhar

o concurso de samba-enredo em duas escolas do Grupo Especial de São

Paulo é uma resposta a tudo isso", acredita Jairo. Ronny concorda e

protesta: "Não ter raiz do samba no sangue sempre pesou como um estigma

sobre a gente".

Nessa cruzada contra o preconceito, ambos

defendem o direito de se expressar como cidadãos brasileiros apaixonados

pela arte do samba e sua expressão mais popular, que é o Carnaval. Ser

judeu é um detalhe que, evidentemente, não deveria ter o menor

significado, como não tem o fato de a passista ser católica, o

mestre-sala ser umbandista, o mestre de bateria ser devoto de Ogum – e

de São Jorge ser considerado protetor dos batuqueiros.

Uma boa

demonstração de que é possível conviver com a tolerância religiosa é o

desafio que este ano caiu nas mãos de Ronny. Como Carnavalesco da escola

X-9 de Santos, ele tem a missão de levar para a avenida um desfile

sobre a importância de Nossa Senhora de Monte Serrat para a história da

cidade, da qual é padroeira. Caberá, pois, a um judeu a nobreza de se

despir dos preconceitos para encenar na avenida os tantos milagres que

são atribuídos à santa da Igreja católica, mostrando em suas criações a

diversidade presente na essência do Carnaval.

(

UOL)

Também disponível no Street Striker